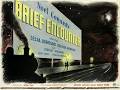

A protester

gestures as Uber and Lyft drivers drive through Beverly Hills on Wednesday to

demonstrate outside the $72m home of the Uber co-founder Garrett Camp.

Photograph: Mark Ralston/AFP via Getty Images

Uber

reported losses that would make WeWork blush – and that's the good news

Ride-hailing

companies are stepping up their fight against new worker protections. They want

drivers to help

Julia

Carrie Wong in San Francisco

@juliacarriew Email

Thu 7 Nov

2019 11.01 GMTLast modified on Thu 7 Nov 2019 16.42 GMT

It feels a

bit Alice in Silicon Valleyland, but the good news for Uber this week was that

it lost $1.2bn in the third quarter of 2019. While burning that kind of cash in

90 days would make even WeWork’s Adam Neumann blush, it is an improvement over

the previous quarter’s jaw-dropping deficit of $5.24bn.

Uber’s

latest financial results came just two days before its post-IPO lockup period

expired on Wednesday, allowing early investors and employees to cash out and

touching off a stock sell-off that saw the share price reach a new all-time

low. Hundreds of Uber drivers across California marked the occasion with

protests targeting some of the handful of people who have unambiguously

benefited from the Uber economy. Drivers visited the home of the early investor

and former board member Bill Gurley in Atherton and the $72.5m mansion of the

co-founder Garret Camp in Beverly Hills.

The

company’s fraught relationship with its workforce is only going to get more

complicated over the next year, as the fundamental question of Uber’s existence

– are drivers employees or independent contractors? – is put to the test in its

home state.

Uber,

together with Lyft and DoorDash, took the first steps this past week to fight

back against a landmark bill, AB5, that would jeopardize the contractor status

of ride-share and delivery drivers. On 28 October, the three companies filed

the paperwork to begin a campaign for a November 2020 ballot measure that would

exempt them from the new rules for classifying workers.

They were

following through on their August pledge of $30m for the initiative – a

last-ditch attempt to scare state lawmakers off passage of the bill. The

legislature did not blink, and Instacart and Postmates have since thrown in

$10m apiece of their own, putting the nascent campaign on track to be one of

the most expensive in California history.

Uber and Lyft have wasted no time in

leveraging their relationships with drivers to advance the campaign

Uber and

Lyft have wasted no time in leveraging their relationships with drivers to

advance the campaign. Drivers who log on to Lyft to work are shown a screen

urging them to sign up in support of a “ballot measure to preserve your freedom

and provide new protections and benefits”, while Uber sent emails urging

drivers to “vote yes to protect driver choice and flexibility”.

There are

no limits on the amount of app-based campaigning like this that Uber and Lyft

can do under California law, according to Bob Stern, former president of the

Center for Governmental Studies. That means the ride-hail experience in

California is likely to become heavily politicized over the next year. Think

app notifications urging you to vote or campaign flyers delivered alongside

your takeout food. Signature gathering is a quintessential, pre-gig-economy gig

in California, and it may be only a matter of time before ride-hail companies

begin offering drivers bonuses to carry petitions and gather signatures in

their cars.

In

conversations inside Facebook groups for Uber and Lyft drivers, workers are

divided over support for AB5 or the ballot measure – and distrustful of any

claims that their working conditions will ever improve. The ballot measure

promises an “earnings guarantee” of 120% of the minimum wage, provides a

$0.30-per-mile reimbursement for gas and other expenses, and offers a stipend

for healthcare for those who drive at least 15 hours a week. But an analysis by

the UC Berkeley Labor Center – dismissed as “absurd” by the campaign – found

that loopholes in the initiative mean that drivers would only be guaranteed

$5.64 an hour.

Uber has

both claimed that AB5 does not apply to it – and treated it as an existential

threat. In its financial filings, the company acknowledges that classifying

drivers as employees would require it to “fundamentally change [its] business

model”. Also acknowledged in those filings is another unhappy fact: over the

course of its existence, Uber has lost $15.3bn.

At some

point, another fundamental question will need to be answered: is this business

model even worth preserving?

.jpeg)

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário