Push review – a whirlwind tour of rocketing rents and personal tragedy

4 / 5

stars4 out of 5 stars.

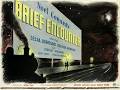

This

powerful documentary, about a UN investigator travelling the planet to get to

the bottom of the global housing crisis, lays bare a $217 trillion scandal

Oliver

Wainwright

@ollywainwright

Tue 10 Sep

2019 17.39 BSTLast modified on Wed 11 Sep 2019 11.07 BST

‘Idon’t believe that capitalism itself is

hugely problematic,” says Leilani Farha, as she marches along a pavement in

Harlem, New York. The UN’s special rapporteur on adequate housing is on her way

to visit a sprawling low-income housing project that was recently acquired by a

private equity fund, leading to massive rent hikes and probable evictions. “Is

unbridled capitalism in an area that is a human right problematic? Yes.”

The

conflict between rights and profits lies at the heart of a thought-provoking

documentary, Push, which follows Farha’s forays into the bleak depths of the

global housing crisis, as she attempts to unpick exactly how we got here. In

the Harlem estate she meets a man who already spends 90% of his income on his

rent. Soon, his two-bedroom flat will cost $3,600 (£,2920) a month, and he will

be forced to move.

It is a

story repeated from Toronto to Berlin, Stockholm and Seoul – via London’s

cleansed Heygate Estate and the remains of the Grenfell Tower – where Swedish

director Fredrik Gertten accompanies Farha on a whirlwind tour of personal

tragedy and corporate greed, as she unearths familiar tales of poor residents

being forcibly evicted to make way for luxury investment units to be sold to wealthy

overseas buyers.

Her task is

an unenviable one. On the one hand is a $217tn (£176tn) global property

business, worth more than twice the world’s total GDP. On the other is the

human right to adequate housing, which is referred to in the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights and recognised in international human rights law

under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of

1966. This law has been flagrantly breached by practically every UN member

state ever since. In the middle, providing an engagingly human presence on

camera, is Farha, the plucky 50-year-old lawyer and housing advocate from

Ottawa. “I’m 5ft 2in, I’m from this nowhere place, and I’m trying to make a

huge difference globally,” she says, looking out of a window at blurred ranks

of high-rise condos. “I’m trying to change an entire conversation that’s embedded

in the way people live all around the world.”

Along the

way, providing sage guidance in her quest, are the voices of sociologist Saskia

Sassen and economist Joseph Stiglitz, heavyweight academics who dispense

bullets of wisdom. Sassen has spent her career analysing the invisible global

flows between world cities. She is frank: “This is not at all about housing.

The buildings function as assets.”

She places

the blame firmly the finance industry, which “sells something it does not have”,

and which to do so “needs to invent brilliant instruments that allow it to

invade other sectors” – mechanisms that are sadly beyond the scope of the film

to explain. (It could have done with a few rapid-fire explainers, in the style

of The Big Short). Sassen compares the financial industry to mining: “Once it

has extracted what it needs [from housing], it doesn’t care what happens to the

rest.”

The Nobel

laureate Stiglitz illuminates exactly how the world of private equity invaded

property thanks to the 2008 financial crisis, in a process that was facilitated

by the US government. “Rather than helping the homeowners who were losing their

homes, [the government] sided with the banks. They encouraged foreclosures to

clean up the books, gave the money to the hedge funds and private equity firms,

who then bought the distressed assets to make money. It’s the way the 2008

crisis has played an important role in increasing wealth inequality.”

Private

equity firm Blackstone emerges as the chief villain of the piece, popping up in

different guises around the world as the faceless Bond baddie lurking behind

impenetrable walls of smoked glass. In the years after the financial crisis,

Blackstone spent about $9.6bn (£7.75bn), hoovering up thousands of properties

across the US, and is accused of hiking rents and ruthlessly pursuing eviction

for nonpayment.

Blackstone

was the company behind the acquisition of the Harlem project, while Farha also

traces its tentacles to Sweden, where it is already the biggest private owner

of low-income housing, having only entered the country in 2014. She visits a

housing estate in Uppsala that the company is currently upgrading – though

Blackstone strongly deny the claim, made in the film, that they have raised

rents by around 50% in the process. Sadly, a momentous meeting between Farha

and Blackstone’s head of real estate falls through, so the company’s side of

the story is absent. (Blackstone say that they spend billions renovating homes,

that they are responsible property managers, and that tenants have a high level

of satisfaction.)

The

iniquitous role of tax havens gets a look-in, too, elucidated by Roberto

Saviano, the Italian author of Gomorrah, the book-turned-TV-series that exposed

the inner workings of the mafia. Now living under police protection and driven

around in a bulletproof car, he explains how offshore companies work in the

property money-laundering business. “You buy things with legal money – a

restaurant, hotel or houses – then you sell those properties to your company in

a tax haven. If you want to bring your dirty money back into your country, you

simply buy it from yourself at a much higher price than you paid.”

As a

result, he says, “companies don’t want inexpensive real estate. They want to

pay as much as possible, to be able to hide more money.” With prices topping

tens of millions for a townhouse, it won’t surprise many that London property

has become the ultimate industrial laundry for the world’s dodgy cash.

Just as you

expect the documentary to reach a dazzling denouement, it rather fizzles out,

concluding with a round-table meeting of mayors pledging to do a bit better.

Nor is it ever explained what the UN’s powers to enforce the right to housing

might be, apart from Farha writing angry letters to the member states. The

passionate special rapporteur is shown presenting her findings to a chamber of

delegates, who fiddle with their phones as she details the catalogue of

catastrophes.

Governments

must wake up. The transformation of cities into playgrounds for the rich, while

homelessness continues to rise, is not an inevitability. It is the result of

structural economic policies, which can be changed – if the will exists.

• Push

premieres at the Barbican, London, on 11 September, as part of the Architecture

Foundation’s Architecture on Film programme, followed by a Q&A with

director Fredrik Gertten

.jpeg)

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário