The last

East German

Egon Krenz

has a simple message: ‘I told you so.’

By MATTHEW

KARNITSCHNIG 11/7/19, 4:30 AM CET Updated 11/7/19, 2:05 PM CET

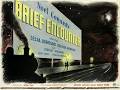

Illustration

by Paul Ryding for POLITICO

BERLIN —

Egon Krenz is sure he’s been here before.

Standing in

the vast lobby of the landmark Hotel de Rome in central Berlin, the last leader

of the German Democratic Republic turns in frustration to a passing employee.

“What was this place?” he asks the young woman.

Unaware of

who Krenz is, she explains that it was originally a private bank and the

central bank of the GDR, the communist East German dictatorship created by the

Soviet Union after World War II.

“I didn’t

come here very often,” he confides to me, flashing his trademark toothy grin.

It’s been a

long time since Krenz, 82, roamed the streets of East Berlin’s former

government quarter, where he spent most of his political career, rising through

the ranks of East Germany’s communist apparatus as the crown prince of the

GDR’s long-time leader, Erich Honecker.

In contrast

to his mentor, Krenz was a strong believer in Gorbachev and immediately

promised “transformation.”

Krenz took

over from his mentor in October 1989, just weeks before the fall of the Berlin

Wall. He spent less than two months in power before his office was abolished to

make way for East Germany’s first free election.

Even if

some of the details of that era have faded with time, Krenz’s take on what

happened remains as sharp as ever. As the 30th anniversary of the fall of the

Wall neared, Krenz, who lives near the Baltic coast, was back in town to hawk

his latest book and set the record straight about the tumultuous events of 1989

and what came after. Wearing a dark sport coat so new he forgot to cut off the

tags, the aging Marxist came to Berlin with a simple message: “I told you so.”

Germany has

turned observance of the Wall’s falling on November 9, 1989 into an annual

ritual to reflect on why the chasm between East and West remains. This year,

the mood has been particularly somber, especially in light of the strong

showing by the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) in a string of states that

once belonged to the GDR.

As the most

prominent living defender of the communist state, Krenz, a large man with a

friendly bulldog face, offers welcome succor to those who feel they landed on

the wrong side of history.

The Berlin

Wall was toppled in November 1989 | Gerard Malie/AFP via Getty Images

“First of

all, the Wall didn’t fall,” Krenz declares after ordering a freshly squeezed

orange juice mixed with soda and ice on the breakfast patio of the old central

bank.

'Gorbi help

us!'

Krenz's

narrative of the dramatic events of 1989 begins in the summer.

Tens of

thousands of East Germans were fleeing the country, most illegally. More than

30,000 left in August alone amid signs the Iron Curtain was cracking from

Poland to Hungary.

By

September, scores of East Germans were taking to the streets in regular

demonstrations to protest against the authoritarian government. Even so,

Honecker, a staunch opponent of Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika policies,

insisted on holding the line and closed the border to Czechoslovakia, the main

route East Germans were taking to get out.

The move

only intensified the pressure. Even as Gorbachev visited Berlin to celebrate

the 40th anniversary of the GDR’s founding on October 7, the demonstrations

continued, with protesters carrying signs reading “Gorbi help us!”

Ten days

later, the East German politburo forced Honecker to step down, replacing him

with his deputy and protégé, Krenz, then 52. In contrast to his mentor, Krenz

was a strong believer in Gorbachev and immediately promised “transformation,”

including liberalizing travel for citizens of the GDR.

Egon Krenz,

left, with Mikhail Gorbachev in early November 1989 | AFP via Getty Images

Krenz, who

thanks to his relative youth was the only member of the GDR’s senior ranks to

have grown up under communism, says he was convinced the country could survive

with open borders by engaging more with the West. “That was an illusion,” he

says today.

An even

bigger misjudgment, though, was trusting Gorbachev, he now says.

On November

1, as rumors circulated that the Soviet Union would drop its support for the

GDR, Krenz visited Moscow, seeking reassurances from Gorbachev.

“The GDR

was a child of the Soviet Union,” Krenz, who studied in Moscow and speaks

fluent Russian, said. “I asked him, ‘Tell me Mikhail Sergeyevich, do you stand

by your paternity?’”

Krenz said

Gorbachev told him he did and that there would be no reunification.

'Storming

the wall'

Krenz says

that during his trip to Moscow, the head of the KGB warned him there were

reports that protesters might try to storm the Brandenburg Gate during a

demonstration planned for November 4. Krenz says he ordered the area, which is

where the Soviet embassy was located, to be fortified. He issued a separate

order to the border police not to shoot demonstrators “no matter what.”

Several

days later, the East German leadership finalized its plans to lift travel

restrictions. On November 9, Krenz handed the details of the decision to Günter

Schabowski, the politburo official charged with announcing the policy to an

international press conference scheduled for that evening. The new regulations

were supposed to take effect the next day, November 10.

But in a

now famous exchange with reporters, Schabowski falsely claimed the opening was

effective “immediately,” prompting thousands of East Germans to rush to the

border that night.

“Honecker

was right about Gorbachev. I believed in him for much too long" — Egon

Krenz, the last leader of East Germany

“What

really happened is that the border was opened at the invitation of a politician

of the GDR,” says Krenz.

The next

day, he wrote a telegram to Gorbachev telling him that of the 60,000 GDR

citizens who crossed the border that night, 45,000 had already returned home

and to their workplace. “Those were very disciplined people storming the wall,”

he jokes.

He remains

convinced that most of his countrymen at the time didn’t really want

reunification but rather a reformed GDR. But the demonization of the communist

regime and promises made by Kohl set a process in motion that couldn’t be

stopped, he said.

Krenz

points out that most of the pictures people associate with the fall of the

Wall, Berliners standing atop the barrier with sledgehammers, were taken well

after November 9. That matters, he argues, because in his mind it was he and

his politburo colleagues who paved the way for a peaceful transition by

suspending the order to shoot and lifting the travel restrictions.

"No

one in a position of power spoke back then of the "fall of the Wall,"

he said.

To

underline his point, he cites a telegram he received shortly afterward from

U.S. President George H.W. Bush congratulating him for “opening” the border.

Footage of

Egon Krenz is projected on the Humboldt Forum building in Berlin, as part of

the festival week to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin

Wall | John MacDougall/AFP via Getty Images

The glow

didn’t last long.

In early

December, Krenz was forced to resign along with the entire politburo. In

January, he was kicked out of the party, which by then was crumbling. Less than

a year later, Germany would be reunified.

“Honecker

was right about Gorbachev,” he said. “I believed in him for much too long. My

relationship to Honecker was destroyed because he knew how much I admired

Gorbachev. Today I know more than I could have then.”

'Everything

would have been different'

Like most

failed communists, Krenz insists that the GDR’s problems weren’t ideology but

execution. “The logic and analysis of Marx’s 'Das Kapital' make it clear that

capitalism cannot be the last word of history,” he says, sipping his third

orange juice and soda.

He's

convinced that what East Germans really wanted wasn’t Western-style democracy

but to be able to travel, own cars and buy electronics. “If we managed to

achieve that on the economic side, everything would have been different,” he

says.

That's why

he's a big fan of the Chinese model. Though not perfect in a socialist sense,

China's communist system has pulled millions out of poverty, he argues.

But what

about the crises of leftist regimes in Venezuela, Cuba and North Korea? All the

result of American efforts to undermine them, he insists.

As a

Soviet-trained politician, Krenz still knows how to parry critical questions

with a flurry of moral relativism and whataboutism.

“I operated

in accordance with the laws of the GDR" — Egon Krenz

The Stasi?

“The CIA has engineered wars,” he says, before citing the revelations of U.S.

spying detailed by WikiLeaks and others.

The GDR’s

infamous prisons? “Up until 1989, no one complained about the conditions

there.”

The scores

of East Germans killed trying to get past the Wall? “I regret every death, but

it was a military zone, there were laws.”

In 1997, a

German court sentenced Krenz to six and a half years in prison, on the grounds

that as a member of the GDR leadership he bore a share of the responsibility

for some of the deaths. Krenz, who served about four years before being

released, still considers the decision “absurd.”

“I operated

in accordance with the laws of the GDR,” he says.

'Reunification

failed'

As one of

the last living links to a country and system that shaped generations of East

Germans, Krenz is not without his admirers. Many former East Germans knew him

from a young age because he was in charge of the communist youth organization.

Krenz says

he receives a regular stream of requests from the children and grandchildren of

GDR old-timers asking him to congratulate their loved ones on a big birthday or

anniversary.

Over the

summer, hundreds of people convened on Berlin’s Russia House, a cultural

center, for the presentation of his latest book, “We and the Russians,

Relations between Berlin and Moscow in the fall of ’89.”

The book

has been a bestseller. It’s easy to see why: Krenz tells East Germans they have

nothing to be ashamed of. Even on the rare occasion when he acknowledges that

the GDR “sinned,” he qualifies the admission by stressing it happened a long

time ago.

“Large

numbers of East Germans feel like second- or third-class citizens,” he says,

referring to a series of recent polls.

He says

that in 1991, he sent Helmut Kohl a study by a Leipzig professor warning that

attitudes in the East were turning and that if the former GDR citizens weren’t

treated with more respect the East-West divide would never be overcome.

“Reunification failed,” he tells me.

That

failure, he says, is largely to blame for the rise of the AfD in the East,

where many Germans, frustrated by a sense that they’ve been left behind, turn

to the populists.

Krenz sees

the answer to most of Germany’s woes, not unsurprisingly, further to the East.

“What we really need to do is to get closer to Russia again,” he says. “Germany

has done best when it’s close to Russia.” (Krenz has never visited the U.S. and

doesn't speak English. He was invited in 1990 but balked when he was asked to

fill out a form that included the question: "Are you a communist?")

Krenz, who

last month celebrated the 70th anniversary of the GDR’s founding with a group

of several hundred comrades, sees his continued allegiance to the ideals of

East Germany as a sign of “character,” not delusion.

“I’m not

sitting here pouting,” he says at the end of our long exchange. “Thirty years

have passed. The GDR is gone and won’t return. I’m a realist. Open wounds? Yes.

It was my life.”

This

article has been updated.

.jpeg)

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário