By Eric

Levitz@EricLevitz

Nine months

ago, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez told a crowd at the Riverside Church in

Manhattan, “The world is going to end in 12 years if we do not address climate

change.” In some respects, the congresswoman’s statement was excessively

optimistic.

If the

climate crisis were as binary and undiscriminating as AOC suggested, it would

be much easier to avert. If 1.5 degrees of warming marked an unambiguous

dividing line between a “healthy” climate and total ecological catastrophe —

which is to say, an equal-opportunity extinction event that would wipe out Xi

Jinping’s daughter and Barron Trump just as surely as it would peasants in

Bangladesh — then carbon-dioxide emissions probably wouldn’t have risen by 2.7

percent last year. The absence of a single do-or-die climate deadline, from

which no country or class is exempt, enables complacency and procrastination,

especially among the aging plutocrats who rule so much of our world.

Meanwhile,

the ambiguities and inequities of the ecological crisis also pose challenges

for mobilizing activists behind climate action. The facts of our predicament

don’t always make for punchy slogans. No one is ever going to rally a crowd by

pumping her fist and shouting:

“We have

already burned an unsafe amount of carbon, and nothing we do now is likely to

prevent the climate from growing evermore inhospitable for the rest of our

lives. We cannot know with certainty quite how much ecological devastation

we’ve already bought ourselves, or exactly how much carbon we can burn without

triggering mass starvation, civilizational collapse, or human extinction. Those

1.5- and two-degree warming targets you’ve heard so much about are informed by

science, but they’re still inescapably arbitrary. Keeping warming below 1.5

degrees won’t be sufficient to prevent wrenching ecological disruptions (some

of which will be tantamount to “end of the world” for those most severely

afflicted). And at the rate we’re going, we almost certainly not going to keep

warming below even two degrees, anyway. A better climate (than our current one)

is not possible; at least, not for us, or our children, or their children. But

the faster we decarbonize the global economy, the better our chances of sparing

the world’s most vulnerable communities from near-term destruction — and our

civilization from medium-term collapse — will be.”

So,

instead, climate activists say things like, “We have 12 years to save the

planet.” And heads of state solemnly swear to “solve” climate change by keeping

warming below two degrees. We tell ourselves stories in order to do politics.

But

Jonathan Franzen is sick of it. In an essay for the New Yorker, the novelist

takes exception to the left’s “pretending” on climate change. Franzen argues

that when figures like Ocasio-Cortez frame the Green New Deal as “our last

chance to avert catastrophe and save the planet,” they are promulgating a form

of climate denial because there is no serious prospect of humanity keeping

warming below two degrees, and thus “the radical destabilization of life on

earth” is already inevitable. Instead of imagining that a globe-spanning

revolution is waiting in the wings, Franzen implores environmentalists to

accept that the political dynamics that have obstructed climate action for the

past three decades aren’t going to disappear in the next 16 months. The “war on

climate change” is no longer “winnable.” Activists should carry on fighting to

reduce emissions through “half measures,” the novelist explains, since it is

still possible to delay the onset of apocalypse. But it no longer makes sense

for the left to insist that climate change must be “everyone’s overriding

priority forever” — or that “gargantuan renewable-energy projects” must take

precedence over the conservation of “living ecosystems.”

There are a

lot of problems with Franzen’s thinking on this subject. But the biggest — and

most ironic — is that the novelist has himself mistaken politically expedient

rhetorical tropes for scientific truths.

Some of

Franzen’s arguments bear a vague resemblance to cogent points.

Before

looking at where Franzen goes astray, however, it’s worth noting what he gets

half-right. Franzen writes that climate change is already guaranteed to produce

“the radical destabilization of life on earth — massive crop failures,

apocalyptic fires, imploding economies, epic flooding, hundreds of millions of

refugees fleeing regions made uninhabitable by extreme heat or permanent

drought.” It is unclear what it means, scientifically, for a flood to be

“epic,” or a fire, “apocalyptic.” But I imagine many residents of Houston,

Texas, or Butte County, California, would say that much of Franzen’s dark

prophecy has already been realized. And the warming we’ve already bought

ourselves will likely be sufficient to implode some economies, cause

significant crop failures, and displace large masses of people. If these are

the defining features of climate disaster, then climate disaster is already

inevitable. And one can plausibly argue that progressive rhetoric elides how

much trouble we’re already in. Climate reporter Emily Atkin assembled a version

of that case for The New Republic last year:

“The whole

idea that everything’s going to work out isn’t really helpful, because it isn’t

going to work out,” said Kate Marvel, a climate scientist at the NASA Goddard

Institute for Space Studies. Climate change is going to worsen to a point where

millions of lives, homes, and species are put at risk, she said. The only thing

humans can do is decide how many lives, homes, and species they’re willing to

lose due to climate change — how long they’re willing to allow their respective

governments to stall on what we know to be technically achievable.

Further,

Franzen’s assessment of our prospects for averting two degrees of temperature

rise is very likely correct. If every signatory of the Paris Agreement honored

its emission-reduction commitment under the accord, the Earth would still be at

least three degrees Celsius warmer than pre-industrial levels by 2100. And only

a tiny fraction of signatories are on pace to honor those commitments.

Thus,

Franzen’s pessimism on this score is neither uncommon nor novel. In fact, New

York Times climate reporter Brad Plumer declared that keeping warming below two

degrees was all but impossible back in 2014 (when he was still writing for

Vox):

By now,

countries have delayed action for so long that the necessary emissions cuts will

have to be extremely sharp. In April 2014, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on

Climate Change (IPCC) concluded that if we want to stay

below the 2°C limit, global greenhouse-gas emissions would have to decline

between 1.3 percent and 3.1 percent each year, on average, between 2010 and

2050.

To

put that in perspective, global emissions declined by just 1 percent for a

single year after the 2008 financial crisis, during a brutal recession when

factories and buildings around the world were idling. To stay below 2°C, we may

have to triple that pace of cuts, and sustain it year after year.

… “Ten

years ago, it was possible to model a path to 2°C without all these heroic

assumptions,” says Peter Frumhoff of the Union of Concerned Scientists. “But

because we’ve dallied for so long, that’s no longer true.”

Five years

later, the path to two degrees requires assumptions even more heroic. So,

Franzen is probably right that we aren’t going to keep warming below that

threshold. He’s just badly wrong about what that means.

Franzen’s

understanding of climate science could use a few corrections.

Even as the

author mocks the baseless optimism of progressive rhetoric on climate, he

treats the center-left’s most convenient rhetorical contrivance on the subject

as gospel: that two degrees of warming (give or take) marks a “point of no

return,” at which the climate “spins completely out of control,” and near-term

civilizational collapse becomes inevitable. “In the long run, it probably makes

no difference how badly we overshoot two degrees,” Franzen writes. “[O]nce the

point of no return is passed, the world will become self-transforming.”

This is

extremely wrong. As David Wallace-Wells writes (in a book that Franzen cites in

his essay, but perhaps did not read very closely):

[G]lobal

warming is not binary. It is not a matter of “yes” or “no,” not a question of

“fucked” or “not.” Instead, it is a problem that gets worse over time the

longer we produce greenhouse gas, and can be made better if we choose to stop.

Which means that no matter how hot it gets, no matter how fully climate change

transforms the planet and the way we live on it, it will always be the case

that the next decade could contain more warming, and more suffering, or less

warming and less suffering. Just how much is up to us, and always will be.

But don’t

take my colleague’s word for it — take co-author of the 2018 IPCC report Myles

Allen’s. “Bad stuff is already happening and every half a degree of warming

matters,” Allen recently wrote, “but the IPCC does not draw a ‘planetary

boundary’ at 1.5°C beyond which lie climate dragons.”

Given both

the technical feasibility of keeping warming below two degrees (or even below

1.5) — and the immense human consequences of every incremental increase in

global temperatures — there is a strong argument for politicians and activists

to hold the line on conventional warming targets, no matter how politically

dubious or scientifically arbitrary they may be. That said, there is a

difference between refusing to acquiesce to political probability, and refusing

to make contingency plans in light of it. Given what the available evidence

tells us about the prospects of rapid decarbonization over the next decade, it

would be grossly irresponsible to oppose investments in carbon capture and

other “negative emissions” technologies. We no longer have the luxury of forswearing

such “moral hazards.” Similarly, given the certainty of wrenching ecological

disruptions, Franzen is on firm ground when he calls on his readers to make

comprehensive preparations for a world of climate chaos:

Preparing

for fires and floods and refugees is a directly pertinent example. But the

impending catastrophe heightens the urgency of almost any world-improving

action. In times of increasing chaos, people seek protection in tribalism and

armed force, rather than in the rule of law, and our best defense against this

kind of dystopia is to maintain functioning democracies, functioning legal

systems, functioning communities. In this respect, any movement toward a more

just and civil society can now be considered a meaningful climate action. Securing

fair elections is a climate action. Combatting extreme wealth inequality is a

climate action. Shutting down the hate machines on social media is a climate

action. Instituting humane immigration policy, advocating for racial and gender

equality, promoting respect for laws and their enforcement, supporting a free

and independent press, ridding the country of assault weapons — these are all

meaningful climate actions. To survive rising temperatures, every system,

whether of the natural world or of the human world, will need to be as strong

and healthy as we can make it.

And yet,

virtually every climate group that’s currently agitating for rapid

decarbonization also supports investments in adaptation and resilience.

Meanwhile, Franzen’s suggestion that supporters of a Green New Deal believe

climate must be “everyone’s overriding priority” — such that no one is allowed

to focus on combating wealth or racial inequality — would be news to both

Ocasio-Cortez and her critics.

Some men

just want to watch the world bird.

Franzen and

climate activists do not disagree on the importance of fair elections and

humane immigration policy. The author builds up the straw man of a green

movement that disdains Black Lives Matter (for failing to focus on the one true

crisis) to build a broader coalition behind his true, idiosyncratic complaint:

that “renewable energy projects” are defacing his favorite bird preserves:

Every

renewable-energy mega-project that destroys a living ecosystem — the “green”

energy development now occurring in Kenya’s national parks, the giant

hydroelectric projects in Brazil, the construction of solar farms in open

spaces, rather than in settled areas — erodes the resilience of a natural world

already fighting for its life. Soil and water depletion, overuse of pesticides,

the devastation of world fisheries — collective will is needed for these

problems, too, and, unlike the problem of carbon, they’re within our power to

solve.

Franzen

articulated this grievance more clearly in his previous, widely panned New

Yorker essay on climate change, in which he voiced frustration at the Audubon

Society’s misguided obsession with climate, and the ostensible willingness of

some so-called environmentalists to “blight every landscape with biofuel

agriculture, solar farms, and wind turbines.” At bottom, his new piece is just

an elaborately elliptical rendering of the same objection. Like President

Trump, Franzen has a visceral distaste for wind turbines and is willing to

distort climate science to rationalize his opposition to massive investments in

renewable energy.

In reality,

stipulating that it is too late to avoid two degrees Celsius warming actually

strengthens the case for prioritizing “renewable-energy mega-projects” over

conservation; since there is no “point of no return” on climate (or at least,

none that we can know in advance), the bleaker one’s assessment of the

prospects for rapid decarbonization, the more committed one should be to

reducing emissions by all practical means.

We don’t

have 12 years to save the world. But we do have the rest of our lives to save

as many of each other as we can. Franzen’s doomerism is for the birds.

What If We

Stopped Pretending?

The climate

apocalypse is coming. To prepare for it, we need to admit that we can’t prevent

it.

By Jonathan

Franzen

September

8, 2019

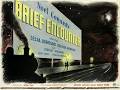

Illustration

by Leonardo Santamaria

“There is

infinite hope,” Kafka tells us, “only not for us.” This is a fittingly mystical

epigram from a writer whose characters strive for ostensibly reachable goals

and, tragically or amusingly, never manage to get any closer to them. But it

seems to me, in our rapidly darkening world, that the converse of Kafka’s quip

is equally true: There is no hope, except for us.

I’m

talking, of course, about climate change. The struggle to rein in global carbon

emissions and keep the planet from melting down has the feel of Kafka’s

fiction. The goal has been clear for thirty years, and despite earnest efforts

we’ve made essentially no progress toward reaching it. Today, the scientific

evidence verges on irrefutable. If you’re younger than sixty, you have a good

chance of witnessing the radical destabilization of life on earth—massive crop

failures, apocalyptic fires, imploding economies, epic flooding, hundreds of

millions of refugees fleeing regions made uninhabitable by extreme heat or

permanent drought. If you’re under thirty, you’re all but guaranteed to witness

it.

If you care

about the planet, and about the people and animals who live on it, there are

two ways to think about this. You can keep on hoping that catastrophe is

preventable, and feel ever more frustrated or enraged by the world’s inaction.

Or you can accept that disaster is coming, and begin to rethink what it means

to have hope.

Even at

this late date, expressions of unrealistic hope continue to abound. Hardly a

day seems to pass without my reading that it’s time to “roll up our sleeves”

and “save the planet”; that the problem of climate change can be “solved” if we

summon the collective will. Although this message was probably still true in

1988, when the science became fully clear, we’ve emitted as much atmospheric

carbon in the past thirty years as we did in the previous two centuries of

industrialization. The facts have changed, but somehow the message stays the

same.

Psychologically,

this denial makes sense. Despite the outrageous fact that I’ll soon be dead

forever, I live in the present, not the future. Given a choice between an

alarming abstraction (death) and the reassuring evidence of my senses

(breakfast!), my mind prefers to focus on the latter. The planet, too, is still

marvelously intact, still basically normal—seasons changing, another election

year coming, new comedies on Netflix—and its impending collapse is even harder

to wrap my mind around than death. Other kinds of apocalypse, whether religious

or thermonuclear or asteroidal, at least have the binary neatness of dying: one

moment the world is there, the next moment it’s gone forever. Climate

apocalypse, by contrast, is messy. It will take the form of increasingly severe

crises compounding chaotically until civilization begins to fray. Things will

get very bad, but maybe not too soon, and maybe not for everyone. Maybe not for

me.

Some of the

denial, however, is more willful. The evil of the Republican Party’s position

on climate science is well known, but denial is entrenched in progressive

politics, too, or at least in its rhetoric. The Green New Deal, the blueprint

for some of the most substantial proposals put forth on the issue, is still

framed as our last chance to avert catastrophe and save the planet, by way of

gargantuan renewable-energy projects. Many of the groups that support those

proposals deploy the language of “stopping” climate change, or imply that

there’s still time to prevent it. Unlike the political right, the left prides

itself on listening to climate scientists, who do indeed allow that catastrophe

is theoretically avertable. But not everyone seems to be listening carefully.

The stress falls on the word theoretically.

Our

atmosphere and oceans can absorb only so much heat before climate change,

intensified by various feedback loops, spins completely out of control. The

consensus among scientists and policy-makers is that we’ll pass this point of

no return if the global mean temperature rises by more than two degrees Celsius

(maybe a little more, but also maybe a little less). The I.P.C.C.—the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change—tells us that, to limit the rise to

less than two degrees, we not only need to reverse the trend of the past three

decades. We need to approach zero net emissions, globally, in the next three

decades.

This is, to

say the least, a tall order. It also assumes that you trust the I.P.C.C.’s

calculations. New research, described last month in Scientific American, demonstrates

that climate scientists, far from exaggerating the threat of climate change,

have underestimated its pace and severity. To project the rise in the global

mean temperature, scientists rely on complicated atmospheric modelling. They

take a host of variables and run them through supercomputers to generate, say,

ten thousand different simulations for the coming century, in order to make a

“best” prediction of the rise in temperature. When a scientist predicts a rise

of two degrees Celsius, she’s merely naming a number about which she’s very

confident: the rise will be at least two degrees. The rise might, in fact, be

far higher.

As a

non-scientist, I do my own kind of modelling. I run various future scenarios

through my brain, apply the constraints of human psychology and political

reality, take note of the relentless rise in global energy consumption (thus

far, the carbon savings provided by renewable energy have been more than offset

by consumer demand), and count the scenarios in which collective action averts

catastrophe. The scenarios, which I draw from the prescriptions of

policy-makers and activists, share certain necessary conditions.

The first

condition is that every one of the world’s major polluting countries institute

draconian conservation measures, shut down much of its energy and

transportation infrastructure, and completely retool its economy. According to

a recent paper in Nature, the carbon emissions from existing global

infrastructure, if operated through its normal lifetime, will exceed our entire

emissions “allowance”—the further gigatons of carbon that can be released

without crossing the threshold of catastrophe. (This estimate does not include

the thousands of new energy and transportation projects already planned or

under construction.) To stay within that allowance, a top-down intervention

needs to happen not only in every country but throughout every country. Making

New York City a green utopia will not avail if Texans keep pumping oil and

driving pickup trucks.

The actions

taken by these countries must also be the right ones. Vast sums of government

money must be spent without wasting it and without lining the wrong pockets.

Here it’s useful to recall the Kafkaesque joke of the European Union’s biofuel

mandate, which served to accelerate the deforestation of Indonesia for palm-oil

plantations, and the American subsidy of ethanol fuel, which turned out to

benefit no one but corn farmers.

Finally,

overwhelming numbers of human beings, including millions of government-hating

Americans, need to accept high taxes and severe curtailment of their familiar

life styles without revolting. They must accept the reality of climate change

and have faith in the extreme measures taken to combat it. They can’t dismiss

news they dislike as fake. They have to set aside nationalism and class and

racial resentments. They have to make sacrifices for distant threatened nations

and distant future generations. They have to be permanently terrified by hotter

summers and more frequent natural disasters, rather than just getting used to

them. Every day, instead of thinking about breakfast, they have to think about

death.

Call me a

pessimist or call me a humanist, but I don’t see human nature fundamentally

changing anytime soon. I can run ten thousand scenarios through my model, and

in not one of them do I see the two-degree target being met.

To judge

from recent opinion polls, which show that a majority of Americans (many of

them Republican) are pessimistic about the planet’s future, and from the

success of a book like David Wallace-Wells’s harrowing “The Uninhabitable

Earth,” which was released this year, I’m not alone in having reached this

conclusion. But there continues to be a reluctance to broadcast it. Some

climate activists argue that if we publicly admit that the problem can’t be

solved, it will discourage people from taking any ameliorative action at all.

This seems to me not only a patronizing calculation but an ineffectual one,

given how little progress we have to show for it to date. The activists who

make it remind me of the religious leaders who fear that, without the promise

of eternal salvation, people won’t bother to behave well. In my experience,

nonbelievers are no less loving of their neighbors than believers. And so I

wonder what might happen if, instead of denying reality, we told ourselves the

truth.

First of

all, even if we can no longer hope to be saved from two degrees of warming,

there’s still a strong practical and ethical case for reducing carbon

emissions. In the long run, it probably makes no difference how badly we

overshoot two degrees; once the point of no return is passed, the world will

become self-transforming. In the shorter term, however, half measures are

better than no measures. Halfway cutting our emissions would make the immediate

effects of warming somewhat less severe, and it would somewhat postpone the

point of no return. The most terrifying thing about climate change is the speed

at which it’s advancing, the almost monthly shattering of temperature records.

If collective action resulted in just one fewer devastating hurricane, just a

few extra years of relative stability, it would be a goal worth pursuing.

In fact, it

would be worth pursuing even if it had no effect at all. To fail to conserve a

finite resource when conservation measures are available, to needlessly add

carbon to the atmosphere when we know very well what carbon is doing to it, is

simply wrong. Although the actions of one individual have zero effect on the

climate, this doesn’t mean that they’re meaningless. Each of us has an ethical

choice to make. During the Protestant Reformation, when “end times” was merely

an idea, not the horribly concrete thing it is today, a key doctrinal question

was whether you should perform good works because it will get you into Heaven,

or whether you should perform them simply because they’re good—because, while

Heaven is a question mark, you know that this world would be better if everyone

performed them. I can respect the planet, and care about the people with whom I

share it, without believing that it will save me.

More than

that, a false hope of salvation can be actively harmful. If you persist in

believing that catastrophe can be averted, you commit yourself to tackling a

problem so immense that it needs to be everyone’s overriding priority forever.

One result, weirdly, is a kind of complacency: by voting for green candidates,

riding a bicycle to work, avoiding air travel, you might feel that you’ve done

everything you can for the only thing worth doing. Whereas, if you accept the

reality that the planet will soon overheat to the point of threatening

civilization, there’s a whole lot more you should be doing.

Our

resources aren’t infinite. Even if we invest much of them in a longest-shot

gamble, reducing carbon emissions in the hope that it will save us, it’s unwise

to invest all of them. Every billion dollars spent on high-speed trains, which

may or may not be suitable for North America, is a billion not banked for

disaster preparedness, reparations to inundated countries, or future

humanitarian relief. Every renewable-energy mega-project that destroys a living

ecosystem—the “green” energy development now occurring in Kenya’s national

parks, the giant hydroelectric projects in Brazil, the construction of solar

farms in open spaces, rather than in settled areas—erodes the resilience of a

natural world already fighting for its life. Soil and water depletion, overuse

of pesticides, the devastation of world fisheries—collective will is needed for

these problems, too, and, unlike the problem of carbon, they’re within our

power to solve. As a bonus, many low-tech conservation actions (restoring

forests, preserving grasslands, eating less meat) can reduce our carbon

footprint as effectively as massive industrial changes.

All-out war

on climate change made sense only as long as it was winnable. Once you accept

that we’ve lost it, other kinds of action take on greater meaning. Preparing

for fires and floods and refugees is a directly pertinent example. But the

impending catastrophe heightens the urgency of almost any world-improving

action. In times of increasing chaos, people seek protection in tribalism and

armed force, rather than in the rule of law, and our best defense against this

kind of dystopia is to maintain functioning democracies, functioning legal

systems, functioning communities. In this respect, any movement toward a more

just and civil society can now be considered a meaningful climate action.

Securing fair elections is a climate action. Combatting extreme wealth

inequality is a climate action. Shutting down the hate machines on social media

is a climate action. Instituting humane immigration policy, advocating for

racial and gender equality, promoting respect for laws and their enforcement,

supporting a free and independent press, ridding the country of assault

weapons—these are all meaningful climate actions. To survive rising

temperatures, every system, whether of the natural world or of the human world,

will need to be as strong and healthy as we can make it.

And then

there’s the matter of hope. If your hope for the future depends on a wildly

optimistic scenario, what will you do ten years from now, when the scenario

becomes unworkable even in theory? Give up on the planet entirely? To borrow

from the advice of financial planners, I might suggest a more balanced

portfolio of hopes, some of them longer-term, most of them shorter. It’s fine

to struggle against the constraints of human nature, hoping to mitigate the

worst of what’s to come, but it’s just as important to fight smaller, more

local battles that you have some realistic hope of winning. Keep doing the

right thing for the planet, yes, but also keep trying to save what you love

specifically—a community, an institution, a wild place, a species that’s in trouble—and

take heart in your small successes. Any good thing you do now is arguably a

hedge against the hotter future, but the really meaningful thing is that it’s

good today. As long as you have something to love, you have something to hope

for.

In Santa

Cruz, where I live, there’s an organization called the Homeless Garden Project.

On a small working farm at the west end of town, it offers employment,

training, support, and a sense of community to members of the city’s homeless

population. It can’t “solve” the problem of homelessness, but it’s been

changing lives, one at a time, for nearly thirty years. Supporting itself in

part by selling organic produce, it contributes more broadly to a revolution in

how we think about people in need, the land we depend on, and the natural world

around us. In the summer, as a member of its C.S.A. program, I enjoy its kale

and strawberries, and in the fall, because the soil is alive and

uncontaminated, small migratory birds find sustenance in its furrows.

There may

come a time, sooner than any of us likes to think, when the systems of

industrial agriculture and global trade break down and homeless people

outnumber people with homes. At that point, traditional local farming and

strong communities will no longer just be liberal buzzwords. Kindness to

neighbors and respect for the land—nurturing healthy soil, wisely managing

water, caring for pollinators—will be essential in a crisis and in whatever

society survives it. A project like the Homeless Garden offers me the hope that

the future, while undoubtedly worse than the present, might also, in some ways,

be better. Most of all, though, it gives me hope for today.

.jpeg)

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário